In In-depth

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

“We are surrounded by an invisible killer,” begins a recent article by the BBC. “One so common that we barely notice it shortening our lives.” We are constantly reminded about the plethora of things that threaten our lifespan; smoking, eating too much sugar, ultra-processed foods, alcohol consumption, lack of exercise – but one that is rarely mentioned is the presence of noise. BBC reporter James Gallagher shed light on this “invisible killer” in an investigation into the impact of noise on our long-term health, noting “its impact on the human body goes far beyond damaged hearing”. Of course, we should be very concerned about the potential damage noise can have on our hearing, but in an increasingly loud world, do we need to be more aware of how it is affecting other aspects of our wellbeing?

Loud and clear

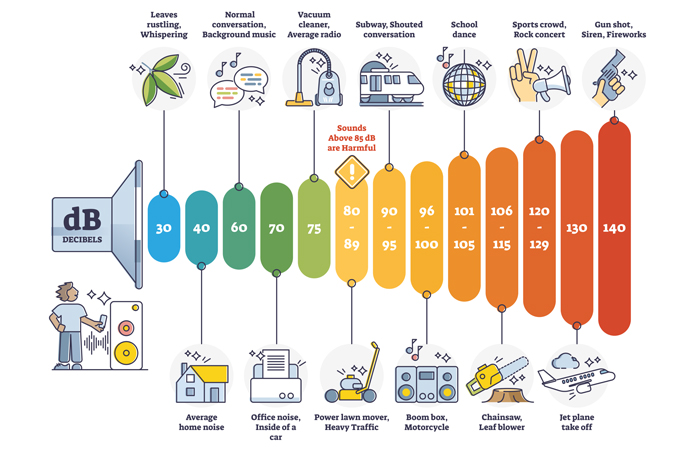

Let’s first understand the difference between sound and noise. Sound is a general term and can be used to describe any auditory experience created by vibrations. Noise, on the other hand, is specifically unwanted or unpleasant sound. Think screeching tubes, loud music, living too close to the train tracks, aeroplanes coming into land and construction sounds – or even the consistent barking of a neighbourhood dog. Anything at around 80dB (decibels) and below is considered a safe and unharmful level of sound. To put things into perspective, see the graphic below for some examples of sounds and how they fair in terms of decibels.

“Loud noises damage the cochlea – our hearing organ in the inner ear, causing permanent hearing loss and tinnitus,” says Richard McKearney, audiology advisor at the Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID). It can also lead to a hypersensitivity to sound. “Some people might not notice the effects of noise-induced hearing loss until years after they were first exposed to loud noise,” and it seems the physiological impact is the same.

When we hear a loud noise, our heart rate picks up as we become agitated – maybe we start to sweat and feel more alert. This is because sounds are not just heard and then forgotten about – our entire body registers a response, and if the sound is too loud, that response can have negative effects.

Noise enters the ear and is then detected by the amygdala in the brain – the ‛emotional centre’. If this small structure in the brain registers a sound as loud and potentially threatening, it triggers the release of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, activating the nervous system and (depending on the severity of the noise, the body may go into fight or flight mode to varying degrees) leading to an increase in heart rate, blood pressure and inflammation in the body. “Over a long time, the constant stress reaction from noise affects the body’s nervous and hormone systems,” says Benjamin Fenech, noise and public health programme lead at The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA).

For many, these sound stresses occur multiple times a day. So, even if they become habituated to planes flying overhead or ambulance sirens down the high street, it may slowly be deteriorating their hearing – which we know accelerates the risk for dementia, depression and cognitive decline – as well as other aspects of health and, as more and more evidence suggests, increasing the risk of premature death.

Making a racket

“Long-term exposure to elevated environmental noise can have numerous negative impacts on human health,” says Benjamin. “Using risk estimates from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region, the European Environment Agency estimated that environmental noise contributes to 12,000 premature deaths due to ischaemic heart disease per year across Europe.” It can also cause or exacerbate type 2 diabetes, sleep disturbances, stress, mental health and cognition problems like memory impairment and attention deficits, childhood learning delays and low birthweight. People whose homes are in noisy environments may find themselves in a constant state of stress or anxiety, neither of which is good for their physical and mental health in the long-term.

Another important thing to consider is the link between good quality sleep and physical and emotional wellbeing. “You never turn your ears off; when you’re asleep, you’re still listening. So those responses, like your heart rate going up, that’s happening whilst you’re asleep,” says professor Charlotte Clark from St George’s University, London. Poor quality and quantity of sleep impacts the amount of restorative sleep an individual gets – the stage where the body repairs tissues, builds muscle, strengthens the immune system and consolidates memory. It can also lead to waking up feeling frustrated, irritable and emotionally exhausted, impacting daytime cognitive alertness.

What the research says

“However, to fully understand the burden of disease due to environmental noise, it is important to consider the cost of living with health conditions as well as the number of premature deaths,” says Benjamin. To do this, researchers use a standard, internationally recognised metric called Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). “The DALY is a time-based measure that combines years of life lost due to premature mortality and years of life lost due to time lived in states of less than full health. One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health,” adds Benjamin.

Findings from an article, Spatial assessment of the attributable burden of disease due to transportation noise in England, published by the UKHSA in Environmental International in 2023, mapped the effects of transport noise on health and wellbeing across England, which “estimated that transport noise in England was responsible for the equivalent of 127,000 healthy life years lost in disability in 2018,” says Benjamin. “These estimates include the disease burden from high annoyance [people who are very bothered or disturbed by noise over a long period of time], high sleep disturbance, ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and stroke.” Some 97,000 of these were lost due to road traffic, 13,000 from railway, and 17,000 from aircraft noise. “Annoyance and sleep disturbance accounted for majority of the DALYs, followed by strokes, IHD and diabetes,” found the article.

Where people lived had a significant impact on the number of disability adjusted life years lost. London, the Southeast and Northwest regions the highest number of road-traffic DALYs lost, with London contributing 63 per cent of all aircraft noise DALYs lost. The article concluded: “Our study shows that transportation noise exposure, particularly from road-traffic sources, is responsible for significant disease burden in England and this varies unequally across regions and Local Authority Districts.” It went on to note that: “Quantifying the disease burden is the first step in building an environmental, social and economic case for action.”

This issue of noise pollution is a big one, which requires collaborative action amongst national and local Government, environmental health practitioners, acoustics specialists, industry, the third sector and affected punlic to solve. In the meantime, being aware of the impact of noise on one’s health is a step in the right direction. And, perhaps, the next time things are feeling a bit too loud, make that a step in the direction of a quieter space.

How pharmacy can help

To avoid permanent hearing loss, tinnitus and hypersensitivity to noise, pharmacy teams can advise customers on the various options to protect their ears. “Noise-induced hearing loss is preventable by avoiding exposure to loud noises,” says Richard McKearney, audiologist advisor at the Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID). “If you’re listening to music through headphones, don’t go over the ‘safe’ volume level of the device and use a safe volume limiter (if there is one on your device). Turn down the volume. Take regular breaks of at least five minutes to five your ears a rest.”

Customers who are worried about the impact of the loud volume at concerts can also “use earplugs designed for hearing protection” and “stay away from the speakers”, advises Richard. For those who are worried about being exposed to unhealthy levels of noise in regular settings as well as those where noise is anticipated, ear protectors like earplugs are an option.

“Ear protectors designed for hearing protection and ear defenders to protect your ears from loud noise by reducing the level of sound reaching your ears,” says Richard. “If you’re exposed to loud noises that can damage your hearing, you should use suitable ear protectors.” This advice may be especially pertinent to customers who work in construction, live along flight paths or near airports or even those who get the tube every day.

It is important that pharmacy teams know the signs of hearing loss. “Some common signs that you might have hearing loss include asking people to repeat what they say, struggling to hear on the phone, turning the TV up louder than others want it, and finding it hard to follow conversation in busy pubs and restaurants,” says Richard. The RNID has a free online hearing test which also recommends the next steps for customers, if necessary. This can be found at: rnid.org.uk/check.

Take it to the top

In more serious instances, customers can be signposted or referred to their GP. “Those concerned about their hearing or the impacts of noise on their health should contact their GP in the first instance,” says a Benjamin Fenech, noise and public health programme lead at the UKHSA. “Those who are disturbed by excessive noise should contact their local Council, who will be able to advise them on the most appropriate action. Customers can report a noise problem to their local council using [the] Government’s website at: gov.uk/report-noise-pollution-to-council.” As always, pharmacy teams should encourage regular blood pressure checks, perhaps especially if your pharmacy falls in an area with high levels of noise annoyance like cities or near airports.